Will Rental Vouchers to Prevent Homelessness Make the State Budget?

The legislature is pushing for a statewide rental assistance program that advocates say would be one the largest efforts to combat homelessness in recent memory.

After more than five years living in New York City’s homeless shelter system, Milton Perez has one goal: “to get the hell out.”

The Bronx native has spent much of the last decade being shuffled between different shelters. In recent years, he has applied regularly for permanent housing through the city’s affordable housing lottery, without success.

“Since I’ve been in the system, I’ve developed hypertension, high blood pressure, insomnia, sleep apnea ... and that’s nothing compared to what others have,” Perez told New York Focus, also citing physical injuries, anxiety, and depression. “Not only physically but mentally, this is a very stressful environment.”

The indignities of the shelter system have fueled Perez’s activism with VOCAL-NY, a grassroots group organizing vulnerable New Yorkers. He joined the group about a year ago after years of frustration with being “warehoused in toxic environments,” he said.

In the coming days, work by housing organizers like Perez could culminate in one of New York’s most ambitious programs to create stable housing for the tens of thousands across the state who are experiencing homelessness or are threatened with eviction.

The Housing Access Voucher Program (HAVP) would create a state-funded analogue to Section 8, a federal program that provides vouchers to some 2 million Americans to help them cover the rent. As proposed in the New York Senate’s one-house budget resolution, the program would launch with $200 million in funding for the coming fiscal year.

“Putting $200 million to start the program this year would be the biggest new investment we’ve made in addressing homelessness” in recent memory, Brian Kavanagh, HAVP’s lead sponsor in the Senate and chair of the chamber’s housing committee, told New York Focus.

Passage of HAVP in New York’s final budget this week would mark a “historic victory,” said Paulette Soltani, political director at VOCAL-NY.

“The quickest way to get out of shelters is giving people the ability to pay the rent,” Soltani said. HAVP would do just that, requiring voucher recipients to pay 30 percent of their annual income towards rent and covering the rest, up to 110 percent of the “Fair Market Rent” threshold set by the federal department of Housing and Urban Development.

Ellen Davidson, a staff attorney in the Civil Law Reform Unit at the Legal Aid Society, said that such a program would be a “landmark.”

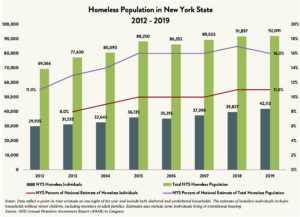

“We were at a moment before Covid where we had record amounts of people who were homeless in our state,” she told New York Focus. Federal data published this month show that even before the pandemic, New York’s homeless population had risen by 44% in the past decade—by far the sharpest increase in the country—to more than 91,000 people sleeping in shelters or in the streets each night.

“We also have large numbers of tenants in the state who are housing insecure, are doubled up, are paying huge portions of their income toward their rent—and the state has thus far done nothing to help people in this situation,” Davidson added.

Legal Aid began advocating for a Section 8-style program at the state level after concluding that the federal vouchers were “one the most successful programs that has helped our homeless clients get into permanent housing,” Davidson said. Massachusetts and Connecticut have operated such programs alongside federal vouchers for decades, and many affordable housing advocates say New York is overdue for a similar approach.

HAVP was introduced in the Senate just before the pandemic but did not make it out of committee in the 2020 session. This year, the measure gained the backing of Senate leadership and was included in the chamber’s budget proposal along with a host of other progressive priorities.

Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie also signaled his support for HAVP on Twitter, after VOCAL-NY held a vigil outside his office. The program was not included in the original Assembly budget, but Social Services Committee Chair Linda Rosenthal told New York Focus that this was an unintentional omission and that Assembly Democrats are committed to pushing HAVP in budget negotiations alongside the Senate.

“It is outrageous that in this wealthy country and in this uber-wealthy state… there are so many New Yorkers suffering on the streets,” Rosenthal said, adding that the $200 million plan would be a major first step to addressing the issue but that “ultimately we’ll need a lot more money.”

In addition to HAVP, the Senate’s budget includes another new homelessness prevention program, the Housing Our Neighbors with Dignity Act, which would put $250 million towards converting distressed New York City hotels into permanently affordable housing. The Senate and Assembly budgets both also contain about $950 million for public housing authorities across the state, more than double the $418 million proposed in Governor Andrew Cuomo’s executive budget.

That’s in addition to distributing $1.3 billion in new pandemic-related emergency rent relief from the December 2020 stimulus bill, which lawmakers and advocates are fighting to ensure actually goes to tenants in need—unlike much of the relief allocated to New York in the first two rounds of stimulus.

The Senate and Assembly’s housing measures would invest significantly more than proposed in Cuomo’s executive budget, whose main homelessness prevention plank is to continue capital programs to build affordable housing, including funding the Homeless Housing and Assistance Program, a program that creates permanent supportive and affordable housing, at last year’s level of $128 million.

Kavanagh told New York Focus that such programs are important but haven’t been enough, given dire rates of homelessness across the state.

“The quickest way to change the dynamic is subsidizing existing housing, while continuing to work on building more housing,” Kavanagh said. The state already has several rental assistance programs, administered through local social services agencies and geared towards emergency situations, he added, “but they just haven’t been funded adequately.”

Kavanagh stressed that HAVP aims to create a “stable resource,” in contrast to the current patchwork of short-term supports. Like Section 8, HAVP would be administered through local public housing agencies, not social services, and stipulates that leases it pays for should generally be no less than a year long.

"A purgatory that you can't get out of"

HAVP would join a long line of programs, ranging from the local to the federal level, aiming to help New Yorkers pay the rent. The largest is the federal Section 8 program, which in 2018 provided portable vouchers to 229,000 New Yorkers. But Section 8 only covers a small fraction of those eligible for the benefits—about 1 in 4 nationally—leaving most renters on their own.

New York’s efforts to close that gap are overwhelmingly geared towards New York City, with a range of emergency assistance programs consolidated under Mayor Bill de Blasio into the Family Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement (CityFHEPS). These programs cost at least $134 million in 2019 (funded mostly by the city), but critics say they fail to reach most people who need them.

Of the people who were granted CityFHEPS vouchers in 2019, only around 20 percent found apartments within a year, Councilmember Stephen Levin told New York Focus. That rate is a key reason why the average shelter stay in the city is 450 days, he said, leaving residents “locked into a purgatory that you can’t get out of.”

Levin is the sponsor of a Council bill aiming to address one of the biggest obstacles for CityFHEPS: “It just doesn’t pay.” The vouchers only cover up to 85 percent of the area Fair Market Rent, which leaves the vast majority of apartments out of reach.

Perez, after his many years in the shelter system, only qualified for CityFHEPS when his dorm closed last year and he was moved into a hotel. His voucher would only cover $1265 — significantly below market rent for a studio or one-bedroom even in East New York, one of the city’s less expensive neighborhoods, where he currently lives in a hotel.

Levin’s bill, Intro 146, would increase CityFHEPS allowances to the full Fair Market Rent. Introduced in 2018, the bill has gained the support of a supermajority of the City Council as well as of the real-estate lobby, but not the mayor’s office — on the grounds, Levin said, that the city can’t afford it.

Advocates counter that keeping people in shelters costs the city upwards of $4,000 per month for an individual and more than $7,000 for many families. But money isn’t the only problem plaguing CityFHEPS. Some landlords simply refuse the vouchers, even though it’s illegal to do so.

CityFHEPS also generally requires beneficiaries to qualify for Cash Assistance, which is tied to U.S. citizenship, leaving many undocumented New Yorkers to slip between the cracks. Section 8 also requires legal immigration status.

“The years that I’ve been [in the shelter system], I’ve met many people who have immigration issues who are basically stuck in place,” Perez said. “They have zero to no chance to get out because they don’t qualify for the vouchers that are in place now.”

“I’ve seen people die in the shelter who are getting no help,” he continued.

HAVP would not be restricted by federal immigration status. That feature appeals to Assemblymember Marcela Mitaynes, a member of the legislature’s new socialist flank who represents the heavily immigrant neighborhoods around Brooklyn’s Sunset Park. Undocumented immigrants disproportionately work jobs at poverty wages and without benefits, she said, putting them among those who need assistance the most.

A legacy of austerity

Mitaynes describes the issue of eviction as “very personal” for her: having immigrated from Peru as a child, Mitaynes lived in the same Sunset Park apartment for thirty years before the building was sold and half the tenants pushed out, including her family. She went from paying a stabilized rent of about $200 to $1400 in the private market, spurring her to join the housing movement.

From her new position in elected office, Mitaynes seeks to continue fighting evictions, which she stresses are not just a problem in New York City, but across the state. That’s one reason HAVP has garnered the support of a wide range of lawmakers across the state, from Rochester to Syracuse to the Hudson Valley.

“It’s been ten years of austerity budgets and it’s been ten years that we’ve seen the homeless numbers under this governor just rise,” Mitaynes said.

Shelly Nortz, Deputy Executive Director for Policy at the Coalition for the Homeless, also places much of the blame for New York’s dramatic rise in homelessness over the past decade on the governor.

There has been a “very dramatic cost shift… under the Andrew Cuomo administration,” Nortz told Focus, with the state “withdrawing its financial participation in housing vouchers and shelter costs for New York City in particular.”

Courtesy of the Coalition for the Homeless

Courtesy of the Coalition for the HomelessThe biggest cut in state support for homelessness prevention came in 2011, just after Cuomo took office, when the state pulled $85 million in support for the main voucher program at the time, known as Advantage. The state funding covered more than half of the cost of the program, and without it, Advantage collapsed. The years that immediately followed saw a huge spike in homelessness, worse than even at the height of the Great Recession.

Today, the state contributes only about 10 percent to New York City’s various homelessness prevention programs. The Coalition for the Homeless gave the state an F on homelessness prevention and housing vouchers in its most recent report card.

The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

The Coalition for the Homeless supports HAVP, as a variation on a theme that the group has backed for decades. Its most recent campaign on this issue has focused on a bill called Home Stability Support, which is still pending and which Nortz describes as “complementary” with HAVP.

Nortz raised concerns about some aspects of HAVP’s implementation, saying that local housing authorities have shown reluctance in the past to working with the homeless. And she said that hundreds of thousands of low-income renters will continue to be at the mercy of the market unless the federal government—historically the largest source of housing funding—renews its own commitment to keeping people in their homes.

Still, Nortz said that $200 million for a program like HAVP would be “a big start.”

Perez, for all of his frustrations with his current shelter, is upbeat about HAVP and also about his own prospects for finding a stable home. After years of trying, he recently qualified for an affordable apartment in Brownsville through the city housing lottery. He’s waiting for his spot to be confirmed, but credits the fact that he matched for an apartment at all to another movement victory: a 2019 bill that increased set-asides in the lottery for homeless New Yorkers.

But Perez regrets that finding a home required winning a lottery—“a one in a million thing.”

“Nobody deserves this sort of treatment,” he said.