Two years after passing a landmark climate law, New York has no plan to fund it

Governor Cuomo just approved the largest budget in New York history — and it has virtually no new funding to help meet the goals in New York’s landmark climate law.

This article was published in partnership with Grist.

Earlier this month, New York passed a $212 billion budget loaded with progressive spending wins, including billions in new school funding, relief for undocumented workers, and rental assistance. But one spending area was conspicuously absent: The state’s climate goals, passed with fanfare in 2019, still lack a payment plan.

When New York enacted those nation-leading emissions targets, it pledged to reach economy-wide net-zero carbon emissions by midcentury. But two years out from the passage of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act, or CLCPA, state legislators have again approved a budget with virtually no new funding to support those targets.

Without designated spending, several legislators and climate experts said, the state is not on track to meet its statutory mandates for decarbonization.

“New York State climate politics look like a backyard with a firepit, some wood, a couple matches — but there’s no kindling. Investment just hasn’t really taken off,” said Daniel Aldana Cohen, a sociologist of climate change at the University of Pennsylvania.

New York, which boasts the third-largest economy and some of the highest greenhouse gas emissions in the country, will need an annual investment of about $31 billion per year in combined private and public spending to bring CO2 emissions down to 100 million tons by 2030, a 2017 study by economists at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst found.

“There are always going to be moderates with sticker shock at the price tag,” said Jabari Brisport, a state senator from Brooklyn who entered the legislature in 2018 as part of a crop of socialist climate hawks. “But we can’t repeat the same mistake we saw with Covid, where we were too slow to act at first, and then scrambling to catch up.”

The 2017 study found that total annual investment will need to average 2 percent of state GDP over the next 9 years if New York hopes to inch its way toward carbon neutrality.

But lawmakers said uncertainty over how much investment will be required and where that money will come from — including how much federal aid to expect — may be part of why climate issues haven’t received more state cash.

“In budget talks, you need to rally around a specific number. With climate, we didn’t have a specific number to advocate for,” Brisport said.

Now, climate advocates are gearing up to fight for funding. But their prospects are uncertain.

Decarbonization spending has hardly budged

In the past, clean energy in New York has largely been funded outside the state budget. The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, or NYSERDA, is the main agency in charge of capital spending to help the state reach economy-wide carbon neutrality. Its budget comes mostly from utility ratepayers and from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, a regional cap-and-trade auction.

The agency has sought to bring more renewables to New York by contracting with offshore wind developers and sponsoring power grid improvements.

Yet despite the passage of the climate bill two years ago, NYSERDA’s total program expenditures have remained largely stagnant. In 2018, the agency reported spending around $1.01 billion. In 2020, expenditures hovered around $1.2 billion. Over the last several years, the agency has underspent by about 20 percent, relative to its program budget. Extending that multi-year trend, NYSERDA can be expected to again spend about $1.1 billion this year.

To make matters worse, New York for years has been diverting part of its RGGI money into the state’s general operating budget -- diminishing NYSERDA’s already limited capacity to support clean energy.

“Transfers to the general fund — $23 million every year, for the past 7 years — that money could have been spent on some pretty meaningful programs,” said Conor Bambrick, an analyst with Environmental Advocates of New York. “RGGI was supposed to supplement state clean energy programs, not supplant them.”

The governor’s press releases on the budget have led with a topline figure of $29 billion invested in combined “public and private green economy investments.” But analysts say that number is misleading, since it is cobbled together from ratepayer bills and private capital committed in past years.

“He keeps touting multi-year combinations of various funding flows to get to these big, misleading numbers,” said Pete Sikora, a climate advocate at New York Communities for Change. “It’s just a cover for his failure to fund climate action.”

Solar panels cover the rooftop of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York City. Mark Lennihan / AP Photo

Solar panels cover the rooftop of the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York City. Mark Lennihan / AP PhotoAsked about the ratio of private investment to public funding in the $29 billion figure — how much private capital is leveraged for each public dollar spent — a spokesman for the state budget office declined to answer.

In addition to a lack of funding, environmentalists and policy experts say that New York also simply lacks the manpower to reach its climate goals. Implementation of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act falls under the purview of the Department of Environmental Conservation, or DEC. The agency is also tasked with land acquisition, water infrastructure and treatment, pollution mitigation and cleanup, and a host of other environmental responsibilities.

The DEC’s duties have mushroomed in recent years, according to a report released in January by State Comptroller Tom DiNapoli, but staffing levels and operating funds have not kept pace. In fact, they’ve fallen.

Full-time DEC staff declined by 20 percent from 2008 to 2020, the report found. Between 2010 and 2020, state spending on the DEC’s operating costs fell by 22 percent, after inflation.

As a result of the funding shortfall, DiNapoli warned, implementation of state and federal environmental laws may have suffered.

“We didn’t do nearly enough”

Environmental advocates say part of the reason the CLCPA remains unsupported is that the same progressive coalitions that scored big wins on increased spending for schools and tenants didn’t push hard enough for climate funding.

State Senator Liz Krueger, Chair of the Senate Finance Committee, told Grist and New York Focus that proposals for new climate spending never came across her desk during budget negotiations.

“I spent many months having meetings with groups calling for new revenue, taxing the rich for a master list of things that they wanted the money for, and it was not for this purpose,” Krueger said of climate spending.

Other priorities took precedence over climate, several legislators said.

“We had to fund education, we had to fund rent relief, we had to provide small business relief,” said Michael Gianaris, the second highest-ranking Democrat in the State Senate. “We did reauthorize the bond act to be put to referendum, which could certainly help,” he added. “But we didn’t do nearly enough.”

The only major new source of climate revenue in New York’s latest budget is a ballot measure for a bond act that would, if passed, authorize the state to borrow $3 billion for projects related to natural resources, mostly for flood resilience, land conservation and recreation, fish hatcheries, and wildlife habitats.

A smaller share of that $3 billion in funding would go towards climate change mitigation, including $350 million for retrofitting buildings — making homes more efficient by installing technologies like solar panels or green roofs, and upgrades to reduce urban heat islands.

The bond act, which will first need voters’ approval in November 2022, was first passed as part of last year's budget. But, citing concerns about borrowing amid the coronavirus crisis, the so-called “Restore Mother Nature” act was pulled from the ballot last minute.

Advocates say any environmental funding is welcome, but the bond’s focus is misplaced, since it prioritizes nature conservation rather than climate-heating pollution. Also, they say, it’s way too small.

“‘Every little bit helps’ — that’s what a less cynical person would say,” quipped Eddie Bautista, director of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, a nonprofit network of community organizations.

Several climate experts said the bond’s environmental focus is part of a bigger trend: Older, more established green groups like the League of Conservation Voters edge out the priorities of organizations like the youth-led Sunrise Movement, who are more zeroed-in on carbon pollution.

“Cuomo has taken a lot of meaningful action on climate, but at the end of the day decarbonization doesn’t light him up in the same way that, say, building a bridge or other more traditional infrastructure does,” said one former senior official in the executive chamber.

Climate groups consider tax-the-rich and polluter-pays spending streams

While the CLCPA authorized New York to enact emissions reductions targets, it did not include any funding mechanism for actually meeting those goals. Advocates anticipated the risks of passing a plan without pay-fors, but forged ahead, reasoning that pushing simultaneously for funding would be politically tougher.

The CLCPA “planted the stake in the ground, in terms of requirements,” Sikora said. “I don’t think it was a strategic error to separate out the two.”

Now, two years after the carbon-slashing goals were passed, advocates are vying to fill the gap between the act’s ambitious targets and state appropriations. The Movement for a Green New Deal, which has not yet been introduced as a bill, would look to haul in an estimated $10 billion to $12 billion per year from New York’s richest individuals. The Climate and Community Investment Act, introduced this month in the legislature, would aim to raise $15 billion each year from polluters by charging a fee of $55 per ton of fossil fuel emissions, making dirty energy sources less competitive. Other carbon pricing proposals have been considered for years, but have received little activist energy.

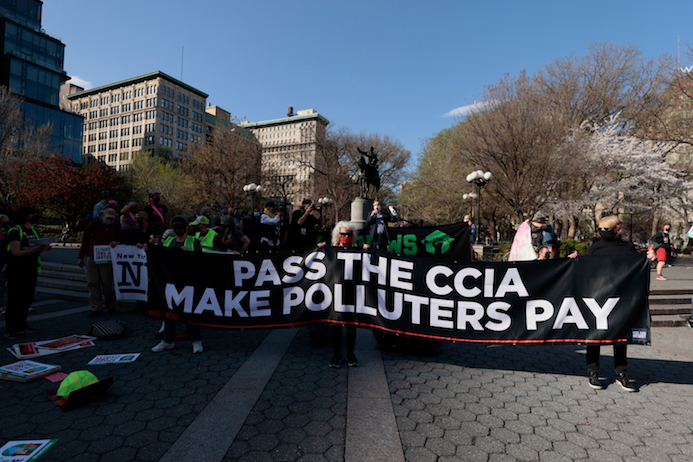

NYC activists rally for the Climate Community and Investment Act in early April. Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Green New Deal Network

NYC activists rally for the Climate Community and Investment Act in early April. Michael Loccisano / Getty Images for Green New Deal NetworkPassing a major spending bill outside the state budget will be demanding, however. Some activists say they would rather focus on trying to get the climate law funded in future budget negotiations.

“The low-hanging fruit would have been to tax the rich. I think we just had our best chance to do that — and won some tax increases, but not on the climate,” said Alex Beauchamp, Northeast Region Director at the environmental group Food and Water Watch. “It’s kind of hard to envision Albany funding something this huge outside of the budget process.”

For now, Sikora said, New York’s ratepayers continue to underwrite “a spray of programs — some of which are effective, some ineffective, all of which are too small.”

“You have the lead politicians, like Cuomo, saying this is an existential crisis, and then they fund it like it’s a pedestrian walkway in some small town,” he added.

President Joe Biden’s infrastructure plan, which would average about $300 billion in annual spending, is expected to finance some climate transition work in New York. But that proposal is just a fraction of what economists say is needed to stave off the worst effects of climate heating — and it hasn’t yet passed.

Some progressive lawmakers, bullish on renewables, see less cause for concern. Krueger, the senate finance chair, is optimistic that renewable prices are coming down so quickly that private industry will lead the way toward decarbonization.

Others, like Gianaris and Brisport, say the state is at risk of blowing past its climate commitments. Governor Cuomo this week declined to rule out permitting more fossil fuel legislation.

New York’s inaction could have ramifications beyond the state — especially as the state has urged federal lawmakers to emulate its carbon-cutting strategy. For example, Biden’s plan proposes to direct nearly half the benefits of its proposed climate investments to “fenceline” areas that have borne the brunt of pollution — a model reportedly inspired by the CLCPA.

New York’s climate law requires that disadvantaged communities receive no less than 35 percent of overall benefits from the law.

“It’s kind of ridiculous because it’s like, a percentage of what?” said Beauchamp. “35 percent of nothing is not much.”