Disabled and Abandoned in New York’s Prisons

Incarcerated people with disabilities detail a labyrinth of humiliations in prison.

Published in partnership with The Nation.

Philip Nelson uses a cane and, when permitted, a wheelchair to navigate Five Points Correctional Facility in upstate New York. At 54, he has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and asthma.

When he attends medical appointments outside the prison, he does so in shackles.

“I am handcuffed with a chain wrapped around my waist, and connected to a black box, so that I am only able to move my hands from my waist to my mouth,” he wrote to New York Focus and The Nation. “I have my feet shackled, which makes it difficult to walk, and even more difficult trying to walk with a cane.”

Nelson has been ordered to push other incarcerated people in wheelchairs, despite needing one himself. Earlier this year, he refused—and was kept in solitary confinement for three days. Another time, he was kept in solitary for being unable to move his belongings to another cell without assistance.

“You are locked in your cell, with meals brought to you, if you are lucky, and have your rec pen opened for an hour a day, if they decide to open it,” he wrote.

Nelson is one of five named plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit filed in August against the Superintendent of Five Points Correctional Facility, the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS), and the Acting Commissioner of DOCCS, alleging that Five Points deprives people with disabilities of their most basic needs.

In a statement, a DOCCS spokesperson said that they do not comment on pending litigation. New York State Attorney General Letitia James’s office, which represents the defendants, filed a response Wednesday, asking the court to dismiss the complaint.

The Five Points lawsuit is far from the first time DOCCS has been accused of discriminating against people with disabilities. In interviews, letters, and grievances, incarcerated people in prisons throughout New York have detailed a labyrinth of humiliations. They’re abandoned in their cells, unable to attend meals. They’re made to lay in their own urine and feces. They’re forced to reuse catheters, resulting in infections and surgeries. Prison staff treat disabled prisoners as a burden whose degradation is deserved.

“The entire system for providing disability related accommodations is broken,” said Torie Atkinson, a staff attorney with Disability Rights Advocates, which filed the suit along with Prisoners’ Legal Services of New York. “Whatever the circumstances are that brought them here, DOCCS is responsible for them now. And they have a responsibility, both legally and morally, to care for these folks.”

Cellbound

Designed as a wheelchair compliant facility that would comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, Five Points Correctional Facility houses approximately 50 to 60 incarcerated people who rely on wheelchairs, walkers, or other mobility devices, according to a 2015 affidavit from the prison’s Deputy Superintendent of Programs.

But inside Five Points, people with disabilities struggle to complete daily tasks—from cleaning their cells to getting to the law library. The City University of New York School of Law’s Disability and Aging Justice Clinic conducted a year-long investigation into Five Points on behalf of four clients, aged 60 to 78. The clinic sent DOCCS their findings, which mirror the lawsuit’s allegations.

“[DOCCS] completely ignored our advocacy letter, except acknowledging receipt,” Natalie M. Chin, the clinic’s co-director wrote in an email to New York Focus and The Nation.

More often than not, wheelchairs are broken or ill-fitting, and pushers—another incarcerated person who pushes a wheelchair—aren’t available. Even when they are, people in wheelchairs are frequently abandoned once they reach their destination.

Robert Cardew, one of CUNY’s four clients, has a heart condition called cardiomyopathy. In 2017, he underwent coronary bypass and aortic valve replacement surgeries; the next year he began to use a wheelchair. Cardew came to prison in 1982, when he was 23. He’s now 62.

In dozens of typed pages, Cardew has chronicled his efforts to attend meals, visit the law library, and go to the recreation yard. He’s filed grievances, sent letters to DOCCS leadership, and, most recently, joined the lawsuit against Five Points.

“[A]bandoned in housing unit looking for someone to push me to mess hall,” Cardew wrote under an entry for June 25, 2019. “I was also told by corrections officer to stay in my cell and never come out because it would make things simpler for them.”

Correctional officers have told him that he has to pay other prisoners to push him, according to his letters to the DOCCS acting commissioner and former-Governor Andrew Cuomo. If he can’t afford to, the officers said, he should “stay in my cell and never come out,” Cardew wrote in a letter to Cuomo in 2019.

At Five Points, people with disabilities are at risk of being disciplined because of their disability. For instance, during outdoor recreation, prisoners must be able to lay on the ground if an incident occurs, according to the Five Points complaint.

"If I do not get face down on the ground in the event of trouble, I will receive an Inmate Misbehavior report,” Cardew wrote to Cuomo.

New York Focus and The Nation requested a copy of this policy from DOCCS and were referred to a general directive about accommodations for people with disabilities.

Fellow plaintiff Khalik Jones is just 39 and suffers from a seizure disorder and a degenerative spine condition. When he arrived at Five Points in 2018, he continued to use the cane he’d received at a county jail and then used while at two state prisons.

But on July 24, 2019, the prison’s nurse confiscated Jones’s cane and ordered him to walk without it. He said he could not. She wrote him up for lying/false information and disobeying a direct order.

“I removed cane from inmate’s hand to obtain more accurate weight and he feigned imbalance,” the nurse wrote in an inmate misbehavior report. “I directed Inmate Jones to ambulate…He refused mouthing silently, ‘I can’t.’ Thereby, disobeying a direct order.”

The charge was ultimately dismissed.

The next month, he fell down the stairs. The nurse accused him of purposely falling. “This writer reviewed the security video of the alleged ‘fall’ and determined it as staff manipulation behavior,” she wrote in an Inmate Misbehavior Report.

At a subsequent disciplinary hearing, the hearing officer watched the video and was “unable to clearly determine if the fall by Jones was on purpose, or on accident,” according to the disposition. The charges were dismissed.

In its response to the lawsuit, the Attorney General’s office denies Jones fell.

Sixty eight-year-old Harrell Bonner, another plaintiff in the suit, said that he has not been disciplined for his disability, but only “because I don’t go nowhere.”

“Once I saw I couldn’t get a pusher I gave up,” Bonner told New York Focus and The Nation through his legal counsel. “If I want to go to rec to play chess, I might have to go [to] the restroom. It’s mind-wrecking when I can’t go. I have to urinate or whatever on myself and I’m tired of that so I just stay in because I can’t get nobody to stay with me or assist me.”

Stonewalling

Little is known about how many people with disabilities are incarcerated in New York, what accommodations, if any, they receive, and where they are housed. Christina Asbee, program director at Disability Rights New York, said that the prison system has stonewalled their efforts to answer these questions.

Litigation, however, provides a glimpse into the macabre reality for people living with disabilities throughout New York state prisons.

In recent years, DOCCS was sued for denying pain medication to people with severe chronic health conditions, denying paraplegic people the proper number of catheters, and for excluding people with disabilities from early release opportunities and some programming, such as access to religious services, the recreation yard, and the law library.

Jose Vega, who is paraplegic, spent more than 20 years incarcerated in New York prisons. In 1997, he sued several prison officials at Shawangunk Correctional Facility for denying him humane medical care.

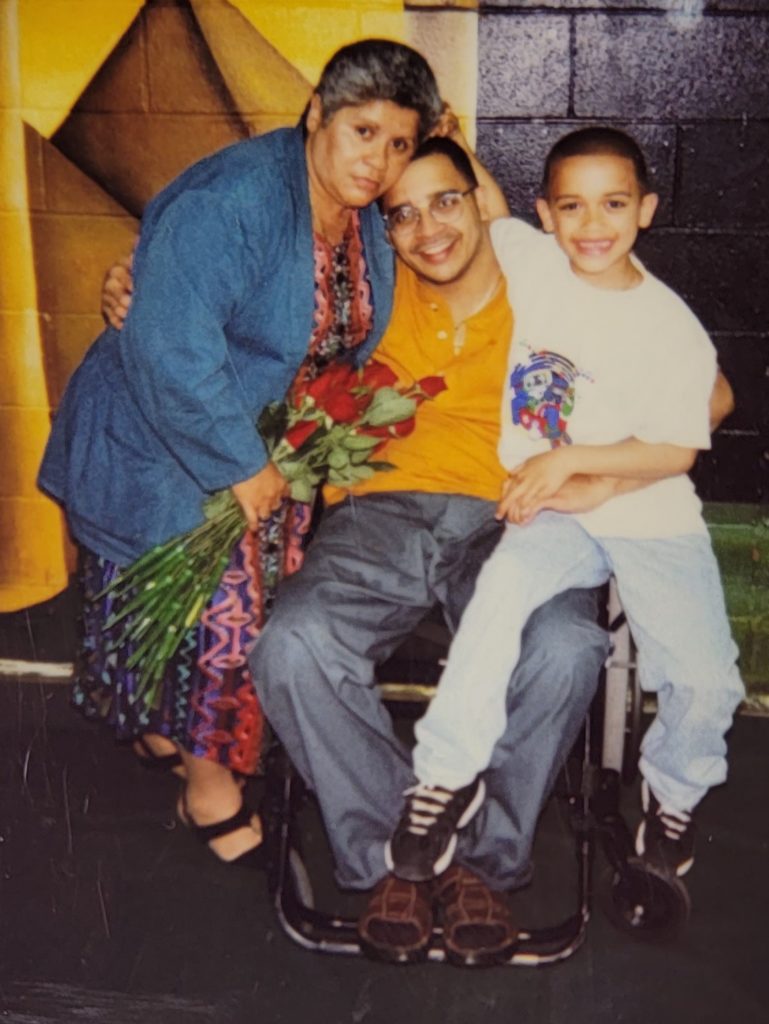

Jose Vega, seen here with his mother and nephew, spent more than 20 years in New York state prisons.

Jose Vega, seen here with his mother and nephew, spent more than 20 years in New York state prisons.“You could be urinating on yourself, you could be full of feces, and they wouldn’t care,” said Vega, who was released on parole in 2018 when he was 47. “They wouldn’t care. They would make fun of you. They would laugh at you.”

Disability rights advocates say that the most urgent priority for the prison system should be to ensure access to working, fitted wheelchairs and trained pushers—but that these changes alone are stopgap measures. Ultimately, elected officials and the parole board have to prioritize decarceration, say civil rights attorneys.

Only 59 people were released on medical parole from 2013 to 2017, about half of whom had died by the end of 2017. Those convicted of first degree murder, attempt to commit first degree murder, or conspiracy to commit first degree murder are ineligible, no matter how old or sick they are. Advocates are pushing for legislation to reform the parole process in hopes that more people will be released from the state’s prisons.

“The best thing would be just releasing people,” said Josh Cotter, an attorney with Legal Services of Central New York. Cotter sued DOCCS for confiscating his client’s motorized wheelchair, which he had brought to prison from home; the court sided with Cotter and ordered the agency to return the wheelchair.

“We have these people that are stuck in the system,” he continued. “They could be with their families and in the community, which would much better serve their needs … No one sees that. [Society says] they did something awful 30 years ago, so they have to stay in prison until they die. It's just an awful way to think of it.”