Renters Powered India Walton’s Upset Win

Renters broke decisively for India Walton in Buffalo’s June Democratic primary, favoring an affordable housing advocate with a tenant-centered housing platform over a developer-friendly incumbent.

This article was published in our Perspectives section. Russell Weaver is a quantitative geographer and Director of Research at the Cornell ILR Buffalo Co-Lab.

In June, democratic socialist and political newcomer India Walton stunned four-term incumbent Mayor Byron Brown, capturing the mayoral nomination in Buffalo’s Democratic primary. Ever since, national media have fixated on the shifting political landscape in upstate New York, even as Brown has vowed to defeat Walton as a write-in candidate in the general election. Framing Walton’s success as part of a broader “Empire State Uprising,” pundits everywhere are eying the emerging “Rust Best socialism” and asking how these upstart left campaigns are uprooting entrenched power dynamics.

While hot takes abound, actual numbers and conclusions with a firm basis in data have been harder to come by. So I got the voter files* from the New York State Board of Elections to find out: who are the voters that led India Walton to a win in Buffalo’s Democratic mayoral primary?

There’s a simple answer: renters.

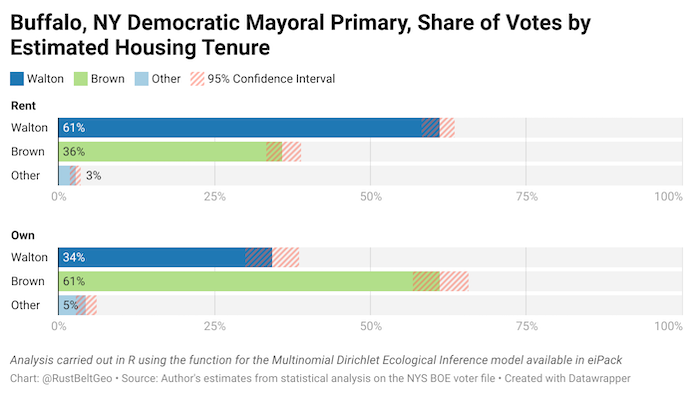

Renters – who, in Buffalo, tend to live in less valuable, lower quality housing and earn less than homeowners – strongly favored Walton over Brown. More than 64 percent of ballots in the primary were cast by people whom the data suggest rent, rather than own, their homes, roughly proportionate to recent Census Bureau estimates showing that about 60 percent of households in Buffalo are renter-occupied.

And my statistical estimates suggest that Walton won that demographic by a landslide, capturing over 61 percent of the renter vote.

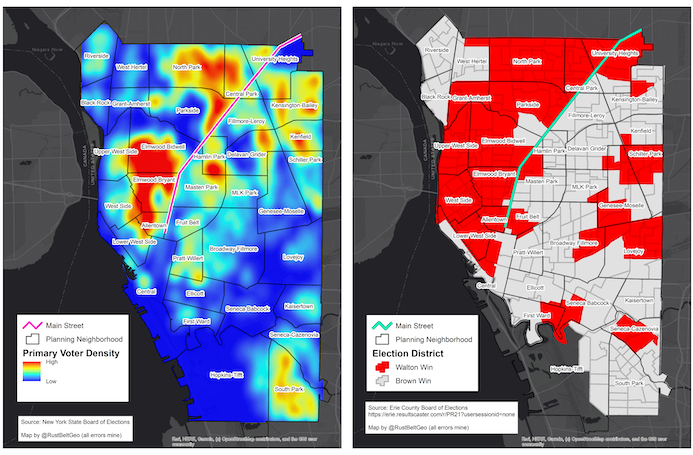

The graphic below shows a heatmap of Primary voters (left) alongside election results (right). Walton won most districts west of Main Street in Buffalo – which consists of younger, racially diverse, mixed-income areas and affluent neighborhoods – but struggled to win in the segregated, low-income, predominantly African American east side of the city.

The districts where Walton had her strongest showings were those with the highest turnout, suggesting an enthusiastic base of support. Brown’s base, meanwhile, largely stayed at home. In one neighborhood favorable to Brown, turnout dropped by two-thirds from the 2017 election, when he won his fourth term.

“There were people in the Black community who couldn’t stomach Brown but didn’t believe India could win,” and therefore chose not to vote at all, Henry Louis Taylor, Jr., a professor of urban and regional planning at the University at Buffalo told the Buffalo-based Investigative Post. “That protest no-vote in the heart of his constituency, which he had not really stirred, blew him away”

The rhetoric from Brown’s campaign hints at why renters might have lacked confidence in his ability to improve the city for them, and thus voted for Walton or simply stayed home: they saw that Brown’s first priority is the owning class.

Betsey Ball, Brown’s Deputy Mayor, said so explicitly in explaining why her boss is running even after Democratic voters rejected him in the primary: “if you have invested in a home, a business, or looking at what has been done by developers, it’s all relevant...you want to see the value of that investment continue,” she told The Buffalo News last week.

Stated another way: if you have an ownership interest in property in the city, then Brown is your candidate. Some of Buffalo’s developers recognize this: Brown’s press conference announcing his write in campaign was held on a property owned by multi-millionaire developer Douglas Jemal.

Mayor Byron Brown: Developers’ Friend

Brown, an establishment Democrat whose campaign is heavily financed by wealthy developers and business owners, and who has looked to conservative Republicans for support following his primary election loss, prioritizes economic growth and the interests of property owners above working people and their neighborhoods.

As an example of Brown’s priorities, the “Growth” section of his website -- which he appears to have scrapped early in 2021 but is still available in archived versions of the site -- featured a paragraph cheerleading the controversial “Buffalo Billion” project as recently as February of this year.

The Buffalo Billion was an initiative announced in 2012 and funded by New York State, with the goal of revitalizing the Buffalo area’s flagging manufacturing economy through grants and tax breaks. The project became a locus of corruption and graft, leading to federal and state investigations and the convictions of multiple state officials and contractors, and largely failed in its intended purpose of economic revival.

While willing to tout this billion dollar failure until earlier this year, Brown has been unable to stem rising home prices or ameliorate a dismal market for renters, and his current campaign website barely mentions housing.

After fifteen years of Brown’s leadership, around 43 percent of households in Buffalo spend more than 30 percent of their monthly income on housing, the federal standard for affordability. Renters are significantly more likely than owners to fall into this category. Compared to a cost-burden rate of just 20.1 percent for owner-occupied housing units, 59.1 percent of renter households struggle with housing unaffordability.

And as Brown and his supporters continue to boast of new dollars flowing into Buffalo’s economy, housing cost burden is worsening. Housing prices have been rising four-to-six times faster than local wages in recent years. More and more residents, especially low-income renters, are struggling to make ends meet as landlords raise rents. One Buffalo-based tenant rights attorney has recently reported rent hikes as high as 55%.

Much of the so-called “resurgence” and reinvestment in Buffalo during Brown’s tenure has been concentrated in high-wealth areas at the exclusion of the city’s poor and working class. That’s a sharp contrast with Walton, whose campaign platform and record as a community organizer both demonstrate a keen concern with providing and preserving quality housing for working Buffalonians.

India Walton: Advocate for Ordinary People

Walton’s platform doesn’t celebrate corrupt billion-dollar boondoggles, as did Brown’s, but rather speaks to the needs of low-income renters. One of her first priorities as mayor is to sign a “tenant’s bill of rights” establishing just cause eviction, the right to counsel in housing court, and rent control, among other reforms. Walton intends to establish a citywide landlord database, so that potential or current tenants can easily track code violations at any given address. She also wants to create a fund to provide one-time mortgage relief for homeowners who fall behind on payments due to unforeseen financial hardships.

And though she’s never before held elected office, Walton has a proven record of providing affordable housing in Buffalo. In 2017, she became the founding executive director of the Fruit Belt Community Land Trust, a nonprofit that creates permanently affordable homes by developing collectively owned properties and placing upper limits on their sale prices.

Under Walton’s leadership, the Trust received $800,000 in funding from New York State to build and preserve affordable housing. Tenants have already moved into some of those houses, and there are plans for dozens more.

Putting Walton’s Win in Context

Rather than seeking to build a coalition of elites on both sides of the political aisle, which appears to be Brown’s strategy; Walton seems to have built, and is working to expand, a pluralistic coalition of the disempowered masses of ordinary Buffalo residents.

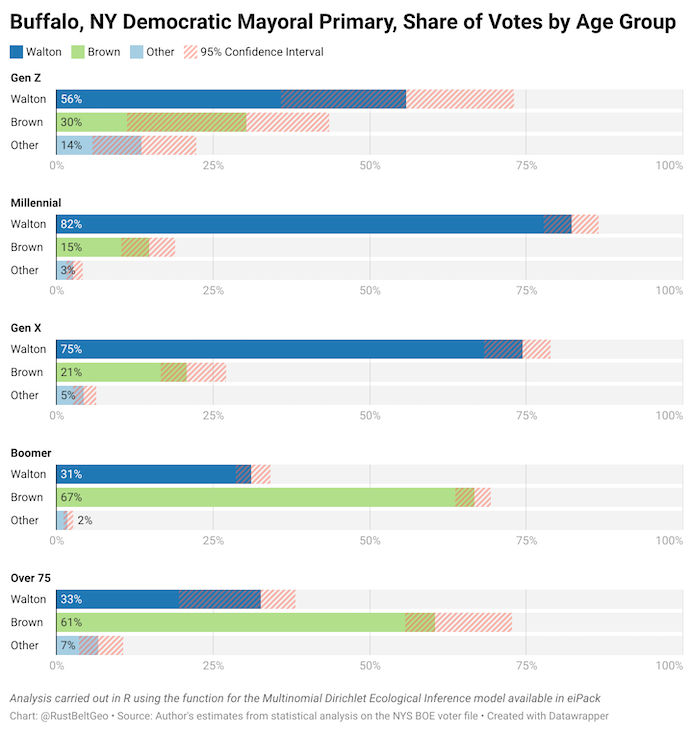

Compared to Brown’s default message of four more years of the status quo, Walton’s bold alternative vision clicked with voters. Apart from renters, she also won handily among young voters. Approximately 82% of ballots cast by Millennials went to Walton. She also won a majority of Gen Zers and around three-quarters of Gen Xers, but lost heavily among older voters, who tend to be averse to anything that smacks of socialism.

Walton’s dominant performances with both renters and young voters are interrelated. Millennials and Gen Zers -- saddled with crushing student debt, having suffered the effects of two major economic crises, and victims of the dual trends of rapidly rising home prices and stagnant wages -- are much less likely than past generations to own their homes. As the U.S. population ages, these younger, financially insecure, predominantly renter-class individuals will become the majority of the electorate. The potential for more India Waltons – candidates who speak to disaffected and precarious working people with visions of how society can be more equitable – to win elections seems likely to grow.

Municipal elections offer the greatest opportunity to this brand of politics: cities have become noticeably younger over the past decade-plus, as Milllennials and Gen Zers have shown a desire for urban living. Given the barriers to homeownership and financial wealth-building that our economic and political systems have set up in front of them, it is not altogether surprising that as voters, these groups are responsive to a brand of politics focused on the material concerns of renters and the working class.

Should Walton go onto victory in November and use the powers of mayoralty to lift people from poverty, investing in community infrastructure, housing, schools, and public services—as Brown seemed disinterested in doing—it might not be long before “Rust Belt Socialism” catches on in cities across the map.